II. The Women in Russell’s Life

II. The Women in Russell’s Life

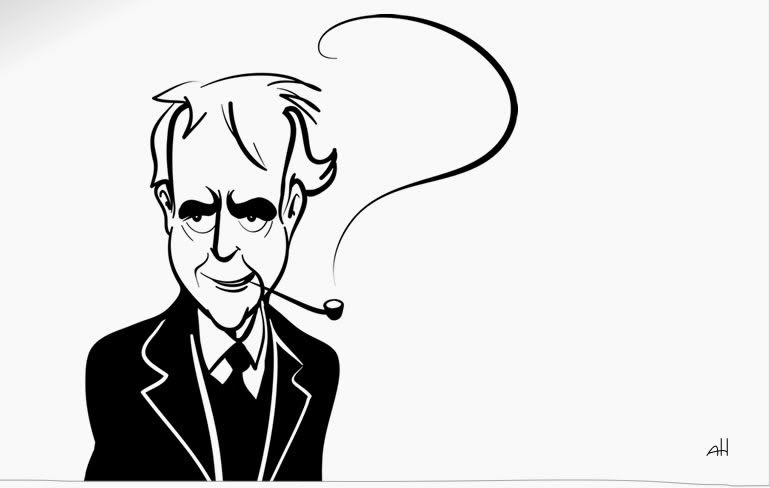

The years that followed saw Russell deluge himself in womanly company. The ladies Ottoline Morrell and Constance Malleson headed the ensemble; and despite Lady Constance’s eminence as an extolled West-End actress, it was the belletristic touch of Lady Ottoline that engrossed Russell’s thirst for self-estrangement. The affair was kindled in 1911, the dawn of a fiercely intense relationship that lasted more than five years. If tradition and conformity lied at the heart of his marriage to Alys, it was surely literature that ran through the veins of his and Ottoline’s liaison. She was a beautiful and well-established aristocrat, known for her influence within the intellectual and artistic circles of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Through the course of her youth Ottoline had befriended a number of the era’s illustrious writers, including Aldous Huxley, Siegfried Sassoon, T.S. Elliot, and D.H. Lawrence—together with a number of others whose work had been bolstered generously by her patronage.[1] Given the high regard in which Ottoline held the arts, and Russell’s longing to become that which he could never be, it comes as no surprise that he spent much of their relationship coveting the gifts of those who occupied her guestbook. He envisaged himself in the grip of an intellectual incarceration, the result of a lifelong pursuit of technical perfection, which left him wretchedly inept to express himself artistically. Pen in hand, he sought to release himself by way of Ottoline’s experience and ‘gentle’ guidance.[2] She, too, felt Russell needed saving: ‘I suppose,’ she wrote him in February 1912, ‘in some mysterious manner I do help you to free the gods and goddesses within you—and to help them all sing together well in tune.’[3] He held the banner of the tragic prodigy, faced with a destiny he could not fulfil, falling short time and time again of his own lofty expectations. Once again Russell had insinuated himself into an atmosphere that smothered him, and in consequence found himself isolated behind towering ramparts of disparity. This peculiar dynamic infused every aspect of the Russell-Morrell relationship, and in time Russell’s determination to become a new person for Ottoline’s sake brought their gluttonous amour to an end. He simply ‘could not turn himself into a writer of fiction,’[4] and in this deemed himself a failure, leaving his once ablaze affections for Ottoline to wither into a tepid cocktail of resentment and laxity. From the remnants of this sour beverage of an affair, however, the pair maintained a lazy friendship that lasted to her death in 1938.[5] Russell, meanwhile, continued his transatlantic rampage: woman by woman the female population was all but consumed by the maw of his libidinous appetite.[6]

Amidst the marrow of the First World War Russell encountered his second wife, one Dora Black, an industrious bluestocking endowed with the progressive philosophy of Britain’s new left wing. They joined forces in 1916 to combat military conscription, an ambition which left Russell held in a six-month incarceration (this time of the physical kind) at Brixton Prison.[7] Upon his release in 1918 he and Dora embarked on something of a travelling splurge, visiting Russia, China and Japan. Illustrated was the pair’s comedic affinity throughout their Japanese sojourn: upon false reports of Russell’s death at the hands of pneumonia, Dora quite satirically informed the press of her companion’s inability to grant an interview on account of his being dead.[8] They travelled together for a number of years, more a cultural investigation than a deluxe retreat, writing regularly on their experiences. Having previously denied Russell’s nuptial advances on the grounds that matrimony restricted the liberty of women, Dora finally ceded to Russell’s wishes upon their return to England in 1921. Given the strength of Dora’s character, and the interests she and her husband shared, one would be forgiven for presuming Russell’s problems here at an end. She fulfilled a role in Russell’s life to which those who precede her would have balked. Together they wrote The Prospects of Industrial Civilization, a feat of collaboration Russell had failed to perform alongside any of his former lovers,[9] and opened a reformist boarding school in West Sussex, an institution which strove to instantiate the educational philosophy of Dora’s In Defence of Children. Dora’s successes came at an expense, however, namely those virtues one could presume attracted Russell to the likes of Alys and Ottoline—ease and normality. Having met more than his match in terms of the progressive ideas of his parents before him, Russell appeared to view Dora’s very liberality as a barrier that stood between them. For the extent of their relationship both Russell and Dora continued to spark relations with other people, a quirk with which he was unlikely to take immediate umbrage; but upon Dora becoming pregnant with another man’s child, the marriage seemed to fall prey to its own progressiveness.[10] The weir of liberal thinking gave way to intense jealousy and bitter resentment, resulting in Russell’s writing of boastful letters describing his youthful conquests across the Atlantic, and his eventual leaving of Dora for their children’s governess, Patricia.[11] He abandoned the campaigns he and Dora had together founded (including their beloved boarding school) and threw himself into the next chapter of his life with bags haphazardly packed.

[1] Simkin, J.. (1997). Ottoline Morrell. Available: www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/Jmorrell.htm. Last accessed 31/01/14.

[2] Moran, M. (1991). BERTRAND RUSSELL MEETS HIS MUSE: THE IMPACT OF LADY OTTOLINE MORRELL (1911-12). McMaster University Library Press. 182-3.

[3] Ibid. 184.

[4] Ibid. 187.

[5] Ibid. 181

[6] Coffey, R.. (2008). 20 Things You Didn’t Know About… Genius. Available: http://discovermagazine.com/2008/oct/01-20-things-you-didnt-know-about-genius#.UwdJWPl_usU. Last accessed 01/02/14.

[7] Simkin, J.. (2013). Dora Russell. Available: www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/TUrussellD.htm. Last accessed 31/01/14.

[8] Russell, B. (2009). Autobiography. London: Routledge. 365-6.

[9] Simkin, J.. (2013). Dora Russell. Available: www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/TUrussellD.htm. Last accessed 31/01/14.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Monk, R. (2001). Bertrand Russell: 1921-1970, The Ghost of Madness. New York: Free Press. 115.